Markov Ducks: The Probability of a Perfect Flock

Written by Alex Cohen and Nikhil Gupta.

One of the most iconic parts of the APS Global Physics Summit is the chance to win a Physical Review journal duck. At the career fair, APS hosts the duck giveaway, where attendees spin a wheel to win one of 12 unique ducks, each themed after a different Physical Review journal.

Duck wheel (left) and close-up of the best duck (right).

On their instagram page, APS presented us with a challenge: “Can you collect ‘em all?”. After the thrill of spinning the wheel and winning our very first ducks, that is exactly what we sought to do. Our first instinct was to jump back in line and continue waiting our turn for more spins. However, with all the interesting talks going on at the conference (and the fact that our advisors didn’t exactly send us there to start a duck collection), we couldn’t justify the uncertainty of potentially waiting in line for hours to complete our duck portfolio. So, we needed to know: how long should we expect it to take to collect all of the ducks?

Nikhil spinning the wheel, hoping for a new duck to add to his collection.

Since we are scientists, we went about answering this question methodically, first by developing an analytical model that describes our system and then collecting data to verify our results. While there are many ways to solve this classic problem (known as the coupon collector’s problem), we decided to use a fun method that, while not the simplest, is general enough to answer many variants of the problem and introduces many interesting mathematical concepts.

In the pursuit of forming a complete duck set, there is just one essential thing that you need to keep track of: how many unique ducks you have collected. We will refer to this number as our state: if we are in state $N$, we have collected $N$ unique ducks. The state we are in after $X+1$ spins depends only on the state we are in after $X$ spins. In other words, your next state only depends solely on your current state. This type of system is known as a Markov chain.

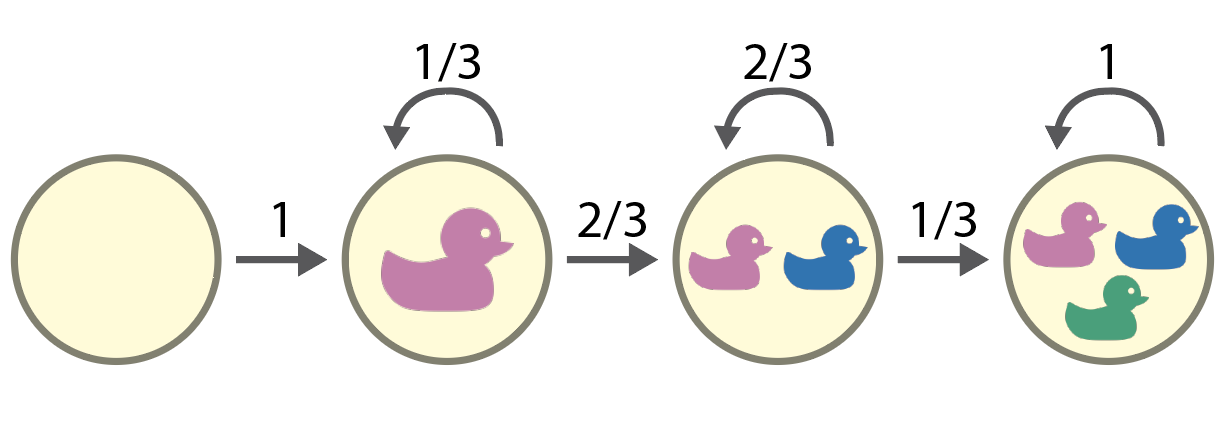

Let’s start by considering a simplified case: a wheel with only 3 ducks. Before our first spin, we start in state 0, a reflection of our duck-less collection. At this point, we spin the wheel and are guaranteed to collect a new duck, moving us into state 1. On the next spin, we have a $\frac{1}{3}$ chance of remaining in state 1 and a $\frac{2}{3}$ chance of spinning a new duck that we have not collected before, which would enter us into state 2. Note that there is no chance of returning to state 0-no one will steal our beloved duck from us! Finally, once we enter state 2, we have a $\frac{2}{3}$ chance of remaining in state 2 and a $\frac{1}{3}$ chance of moving to state 3, in which we have completed our duck collection!

This Markov process can be depicted graphically, where the nodes of the graph represent the state and the directed edges (arrows) of the graph represent the probability of transitioning from one state to another.

Markov model of the three duck wheel.

Now, to estimate the expected number of spins needed to collect all of the ducks, we need to estimate the expected number of steps required to move from state 0 to state 3 in the Markov chain. We will denote the expected number of steps to move from state $i$ to state $j$ in the Markov chain as $E(i \rightarrow j)$. We note that $E(i \rightarrow i) = 0$ since we don’t need any spins to get to the state we are already in.

As mentioned earlier, after the first spin, we are guaranteed to be in state 1, allowing us to simplify our problem to $E(0 \rightarrow 3) = 1 + E(1 \rightarrow 3)$, leaving us to solve for $E(1 \rightarrow 3)$.

Once in state 1, we know that a spin has a $\frac{1}{3}$ chance of keeping us in state 1 and a $\frac{2}{3}$ chance of progressing us to state 2. If we spin and remain in state 1, then our expected number of spins to get to the end will remain $E(1 \rightarrow 3)$. However, if we spin and get to state 2, then our remaining expected number of spins to collect all the ducks becomes $E(2 \rightarrow 3)$. Thus, we can write:

\[E(1 \rightarrow 3) = \frac{1}{3} (1 + E(1 \rightarrow 3)) + \frac{2}{3} (1 + E(2 \rightarrow 3)).\]We can rearrange this equation to get $E(1 \rightarrow 3) = \frac{3}{2} + E(2 \rightarrow 3)$.

By the same logic, we can solve for $E(2 \rightarrow 3)$ using the following equation:

\[E(2 \rightarrow 3) = \frac{2}{3} (1+E(2 \rightarrow 3)) + \frac{1}{3} (1+E(3 \rightarrow 3)),\]which we can once again rearrange to get $E(2 \rightarrow 3) = 3 + E(3 \rightarrow 3)$.

To make things more clear, let us rewrite these equations in reverse order:

\[\begin{array}{rcl} E(3 \rightarrow 3) &=& 0 \\ E(2 \rightarrow 3) &=& 3 + E(3 \rightarrow 3) \\ E(1 \rightarrow 3) &=& 3/2 + E(2 \rightarrow 3) \\ E(0 \rightarrow 3) &=& 1 + E(1 \rightarrow 3) \end{array}\]Here, it becomes clear we can solve for $E(0 \rightarrow 3)$ recursively, simply by plugging in the result from the line above into the line below repeatedly until we get a value for $E(0 \rightarrow 3)$. If we do this process, we find that is $E(0 \rightarrow 3) = 5.5$, indicating that we should expect to spin the wheel 5 or 6 times to collect all three ducks.

This is great for our simplified wheel case, but in reality there are 12 ducks that we need to collect! We could repeat this process for a bigger Markov chain, but that would become very time-consuming, especially with the anticipated growth of the Physical Review duck community in the coming years. So, let’s see if we can spot any patterns and derive a general formula for any number of ducks!

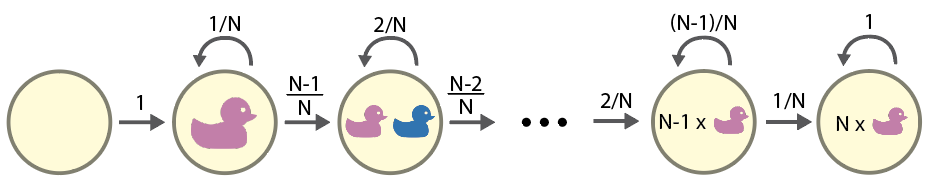

To generalize, let’s say that there are $N$ ducks. Once again, we are guaranteed to get a new duck on the first spin. Now, on the second spin, there is a $\frac{1}{N}$ chance of landing on the same duck you already have, thus remaining in state 1, and a $\frac{N-1}{N}$ chance of spinning a new duck and moving to state 2. Similarly, once you get two ducks, when you spin next, there is a $\frac{2}{N}$ chance of getting one of the two ducks you already have and a $\frac{N-2}{N}$ chance of getting a new duck to move to state 3. This pattern keeps repeating itself, until we have collected every duck except one. At this point, we are in state $N-1$, and, on the next spin, there will be a $\frac{N-1}{N}$ chance of spinning a duck we already have and a $\frac{1}{N}$ chance of spinning the final duck that we don’t have yet. Once again, this process can be graphically visualized as a Markov chain.

Markov model of the N duck wheel.

Now, using the same logic that we used for the 3 duck case, we see that

\[\begin{array}{rcl} E(0 \rightarrow N) &=& 1 + E(1 \rightarrow N) \\ E(1 \rightarrow N) &=& \frac{1}{N} (E(1 \rightarrow N) + 1) + \frac{N-1}{N} (E(2 \rightarrow N) + 1) \\ E(2 \rightarrow N) &=& \frac{2}{N} (E(2 \rightarrow N) + 1) + \frac{N-2}{N} (E(3 \rightarrow N) + 1) \\ &...& \\ E(N-1 \rightarrow N) &=& \frac{N-1}{N} (E(N-1 \rightarrow N) + 1) + \frac{N}{N} (E(N \rightarrow N) + 1) \end{array}\]Once again, we can rearrange all of these equations and write them in the opposite order (you should try this on your own) to get:

\[\begin{array}{rcl} E(N \rightarrow N) &=& 0 \\ E(N-1 \rightarrow N) &=& \frac{N}{1} + E(N \rightarrow N) \\ E(N-2 \rightarrow N) &=& \frac{N}{2} + E(N-1 \rightarrow N) \\ &...& \\ E(2 \rightarrow N) &=& \frac{N}{N-2} + E(3 \rightarrow N) \\ E(1 \rightarrow N) &=& \frac{N}{N-1} + E(2 \rightarrow N) \\ E(0 \rightarrow N) &=& 1 + E(1 \rightarrow N) \end{array}\]Now we are getting somewhere! We can now see that $E(x \rightarrow N) = \frac{N}{N-x} + E(x+1 \rightarrow N)$ when $x < N$ and $E(N \rightarrow N) = 0$. Our $E(x \rightarrow N)$ equation gives us a relationship between each term in our sequence and the previous terms. This relationship is known as a recurrence relation.

Thus, writing out the full series, we get

\[\begin{array}{rcl} E(0 \rightarrow N) &=& \frac{N}{1} + \frac{N}{2} + \frac{N}{3} + ... + \frac{N}{N-1} + \frac{N}{N} \\ &=& N \bigg(1 + \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} + ... + \frac{1}{N-1} + \frac{1}{N}\bigg) \end{array}\]Plugging in $N=12$ into this formula gives $E(0 \rightarrow N) \approx 37.24$.

In fact, the series $1 + \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} + … + \frac{1}{N-1} + \frac{1}{N}$ is known as the (truncated) harmonic series. The sum of these first $N$ terms of the harmonic series is known as the $N$th harmonic number. Thus, the expected number of spins to spin all $N$ unique ducks is $N$ times the $N$th harmonic number.

After determining that each spin takes about 20 seconds, and that the line is usually 15 people long, each of us could spin the wheel once every 5 minutes. Therefore, for each of us to collect every duck, it would take a little over 3 hours!

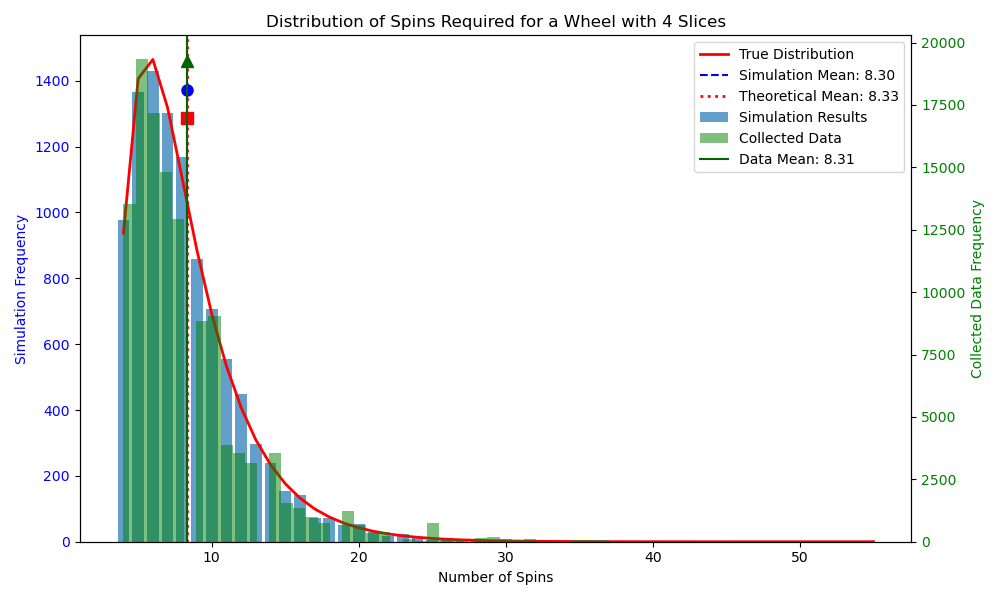

While we didn’t have 3 hours to spare, we still wanted to run an experiment to see all this math manifested as expected in the real world. To do this, we stood nearby the spinning wheel and recorded all the ducks that were spun over the course of 67 consecutive spins. Although the wheel has 12 different ducks, we can group the ducks into 4 groups to get better statistics. For $N=4$, the expected number of spins is 8.33. By considering every possible way to form these 4 groups and recording the observed number of spins it took to collect all the duck pairs for each combination, we measured that it took an average of 8.31 spins to collect a duck from all 4 groups. Even with this small experimental sample size, this result closely matches the analytical result for $N=4$!

To get a better idea of how this converges to the analytical result for larger data sets, we can also run computer simulations of this process. In the plot below, I show the data collection results, the computer simulation results, and the analytical results.

Our mathematical journey through the duck collection problem (classically known as the coupon collector’s problem) revealed that collecting all 12 ducks would require approximately 37 spins on average—equivalent to about 3 hours of dedicated duck hunting at the conference. This playful exploration demonstrates how mathematical modeling can help us make informed decisions, even for something as whimsical as collecting conference souvenirs. Similar probability problems that can be tackled with this Markov modeling approach appear in many contexts in daily life beyond duck collecting and we hope this post provides you with a new way of thinking when you find yourself in a related scenario.

So, can you collect ‘em all? Mathematically speaking, yes—but it might take longer than your conference schedule allows!

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: